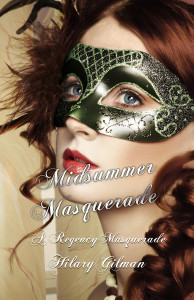

Midsummer Masquerade is finished at last! A Preview!

Finally, after long delays, the next Masquerade book is finished and currently being edited. As my editor is meticulous in the extreme, that might take a while but in the meantime, as usual, I’m posting the first chapter here (the format is not as it appears in the book, I am not that good at ‘tech stuff.’

Finally, after long delays, the next Masquerade book is finished and currently being edited. As my editor is meticulous in the extreme, that might take a while but in the meantime, as usual, I’m posting the first chapter here (the format is not as it appears in the book, I am not that good at ‘tech stuff.’

Midsummer Masquerade has a theatrical background and I have drawn upon a lot of my own experiences, and some old theatrical legends. I have only used theatrical slang that I could prove to have been in use at the time, which wasn’t easy to find. So no ‘corpsing’, ‘drying’ or ‘breaking up.’ Nor have I used’break a leg’ although I’m sure all these phrases had their equivalents. I did use ‘bums on seats’ which has to be as old as the hills, and anyway they use it in Blackadder. If it’s good enough for Richard Curtis….

I found Mansfield Park invaluable. Jane Austen and her family loved amateur theatricals, even though she disapproves when the Bertram family engages in them, so I have assumed without further corroboration that she knew whereof she spoke.

If you would like to be notified when the book is available on Amazon (it will be both a print and e-book) please just post a comment here and I’ll add you to my mailing list.

Chapter One

By the inadequate light of one flickering candle, a young woman was reading a letter. Her face, always expressive, reflected shock, annoyance and finally a kind of weary amusement. As she reached the bottom of the paper she sighed and dropped the hand which held the letter into her lap.

‘Do you know there is blood on your gown?’ Mrs Hargreaves, a lady of some five-and-fifty years, spoke in a matter-of-fact tone as though white muslin soaked in blood were an everyday occurrence: as indeed it was in Brussels in the dark days following the victory at Waterloo. The young woman was lost in thought and so the elder lady said a little more sharply, ‘Philly?’

Miss Ophelia Pitt started and looked up with a sudden smile. ‘I beg your pardon, Ma’am. What did you say?’

‘You should wash out that blood before it is quite dried.’

‘Oh, it will do tomorrow. I’m so very tired.’

‘No wonder. All those hours nursing the wounded and then out half the night looking for that naughty child.’

‘Well, at least we know now where she is.’

‘Do we? I could make neither head nor tail of her note.’

Ophelia laughed. ‘Once I realised that what I had taken to read slope might was actually elopement all became clear. She has, as you so rightly suspected, Ma’am, run off with young De Tournai.’ She lifted a prettily enamelled watch that she wore pinned to her breast and glanced at the tiny face. ‘By this time she is Madame La Comtesse, no doubt.’

‘Very thoughtless and silly.’

‘True. And very inconvenient. There goes my only hope of reaching London by the first of the month.’

‘Perhaps Sir Guy will consent to escort you even though—’

‘Oh I have no doubt he would.’ A rueful smile curled her mouth. ‘Just as Lord Darlington would, or Mr Bainbridge or even old Major Fairfax. And I have no doubt at all that the price I should be expected to pay for my passage would be exactly the same in every case.’

Mrs Hargreaves sighed. ‘Indeed it is a pity you are so very—very—’

‘Very,’ agreed Ophelia, her eyes narrowing in amusement. She knew quite well what her companion was attempting, with delicacy, to suggest. She was a young woman of seven-and-twenty, rather tall, with long graceful limbs, a trim waist, and an exceedingly voluptuous, not to say, magnificent, bust. This attribute when combined with gleaming copper ringlets, heavy-lidded green eyes, and a wide, generous mouth, might not have corresponded to the ideal of beauty then in vogue, as embodied by the wraithlike Lady Caroline Lamb, but it certainly put the most improper ideas into the heads of gentlemen who ought to have known better. Add to this that she was by profession an actress and her scepticism regarding her would-be protectors’ motives was perfectly understandable.

Mrs Hargreaves sighed sympathetically. ‘Would you like some tea, Philly dear?’

Ophelia flashed a sudden, brilliant smile. ‘Oh my case is not so desperate as that! I would not say no to a cognac however.’

‘Well, I do keep a bottle by for purely medicinal purposes,’ admitted Mrs Hargreaves. She rose from her seat and bent to turn up the flame in an oil lamp which stood on a little spindle-legged table beside her chair. ‘I may join you—just to steady my nerves, you know.’

Mrs Hargreaves occupied a somewhat cramped set of chambers at the top of the Comédie Theatre in the centre of Brussels, where she had, for many years, combined the roles of wardrobe mistress and caretaker. The cosy chamber in which they were sitting functioned as sitting-room, dining-room and, since the night of the great battle, Ophelia’s bedchamber. It was furnished with an agreeable selection of chairs, tables, divans and hangings which had previously graced various theatrical productions. A portion of a canvas flat, depicting a sylvan scene of shepherds and shepherdesses frolicking in Arcadian meadows, had been put to use to screen off a section of the room behind which Mrs Hargreaves kept a locked cabinet. Ophelia, who knew perfectly well where the key was kept, turned her head away and hummed a tune in an attempt to ignore the clearly audible clinking of bottles and glasses that came from behind the screen.

Presently the good lady emerged with two tumblers half full of amber liquid. Ophelia took hers with a word of thanks and sipped cautiously. Rather to her surprise it was excellent.

‘Is it unpatriotic to drink French brandy?’ she wondered with a smile.

‘Certainly not! At least–I don’t think so.’ Mrs Hargreaves pondered the question and then said, brightening, ‘This bottle is thirty years old. I don’t think we were at war with France then so— Besides, I don’t think there is any other kind.’

‘Any other kind of what?’

‘Brandy.’

‘Ah!’

They sipped in silence for a while until Mrs Hargreaves presently asked, ‘What manner of man is Sir Guy? Are you acquainted with him?’

‘Not at all. Nor, as far as I know, is Fanny. He has the reputation of being somewhat formidable, which is why, I suppose, she has run away rather than face him.’

‘I don’t know why she could not have simply told him she was betrothed to De Tournai. It is not a bad match. She will be a countess, after all.’

‘From what Fanny has told me, Lord Danehill is one of those Englishmen who believes all foreigners to be inferior. I don’t think a Belgian title would cut any ice with him. And De Tournai’s family has been impoverished by this long war. Even if her grandfather gave his consent there must have been weeks, perhaps months, of delay. Fanny, one can hardly blame her, did not wish to let the Comte go off to Paris leaving her behind.’ She glanced at her friend out of the corner of her eye and her lips curved into a smile. ‘I think there was a very good reason why she wished to be married without delay. One that will become evident in a few months’ time.’

‘You don’t say so!’

Ophelia shrugged. ‘Perhaps I’m mistaken. Well, we shall see.’

She stood suddenly and moved to the window, looking out into the street. As had been the case for days it was unlit but the carts carrying the wounded still rattled over the cobbles and wounded men shuffled behind with the assistance of their comrades. Ophelia watched the scene in silence for a while then broke out suddenly, ‘Oh I could strangle that girl!’

‘My dear! Fanny was thoughtless, no doubt, but a sweeter—’

‘Not Fanny, dear Ma’am, Heloise.’

Mrs Hargreaves shook her head sadly. ‘Your dresser? Yes indeed. That was very bad. And she had been with you for years, had she not?’

‘Yes, three years. I thought she was devoted to me. Hah! To sneak away like that at the first opportunity.’ Ophelia laughed suddenly. ‘I wish I might see her face when she tries to sell those emeralds though.’

The elder lady looked an enquiry.

‘Paste—nothing but paste. Silly creature! Did she really think I would carry the real necklace about with me on tour? It is safe at home in my strongbox with the rest of my jewels but, sadly, they can do me little good there. She has taken all my spare cash and left me penniless. How am I to get to London in time?’

‘Surely Mr Sharp will reschedule rehearsals if you are delayed? After all, the circumstances are quite outside the usual.’

‘Not he! “Sharp by name and sharp by nature” is his boast. He would not consider a little thing like war to be an excuse. I can hear him now. She laughed, thrust her thumbs into an imaginary waistcoat, puffed out her chest and said in a voice quite unlike her own; “Totally unprofessional, Miss Pitt! You should have got here if it killed you!” And that, my dear Ma’am, is the Sharper when he is in an amiable mood.’ She sighed. ‘It is a new play too, written especially for me by Mr Knowles. I had to beg Sharp to let me play in it for he declares that I cannot play anything but comedy. Why, he said my Lady Macbeth was the funniest thing he had ever seen.’

‘Philly, what are you thinking of!’

What—?’

‘You named the Scottish play!’

‘So I did! Well, that just shows you how upset I am.’ She jumped up, ran to the door, opened it, spun around three times counter-clockwise on the landing and spat, nicely, onto her handkerchief. ‘Lord knows, I don’t need any more bad luck.’ She sat down and picked up her glass.

Mrs Hargreaves leaned forward and patted Ophelia’s hand where it lay upon her lap. ‘It was hardly bad luck that caused you to remain behind when the rest of the company had decamped for Antwerp. It was your own dear, brave heart that did that.’

With a rueful smile she answered, ‘Say rather my love of meddling in what does not concern me.’

‘Did those poor boys you nursed and comforted not concern you? Don’t belittle yourself, my love. You have been a tower of strength to me and so many others since our troops marched out upon that terrible, terrible night.’ She shook her head and sighed. ‘I dread to think what would have happened to poor foolish Fanny Howard if you had not found her wandering on the streets and brought her here.’

‘Indeed. Little did I know that I was rescuing, not a stray kitten, but a lost heiress complete with aristocratic suitor, stern grandfather and her very own knight in shining armour about to descend upon us.’

‘I wonder if her grandpapa will have received Fanny’s letter—about being here with me—I mean.’

‘Even if he has not, I left word at the hotel where Fanny was staying with the Fosters, and also with the prefecture of police. I doubt Sir Guy will have any difficulty finding us.’

‘I can understand that Lord Danehill is too infirm to come to Brussels to take home his granddaughter himself, but how comes he to have sent this Sir Guy Gilmour? Are they related?’

‘I know no more than you, but I believe not. Stay—I think Fanny said that he is her grandfather’s godson. She knows very little of him. Has never even met the man. What her grandfather is thinking of to confide her to his charge I really don’t know!’

‘Do you know anything of him?’

‘The grandfather?’

‘No! Sir Guy, I mean.’

‘Why do you ask?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. There is a note in your voice when you speak of him. No doubt I am being fanciful.’

‘No Ma’am, you are not being fanciful. To say the truth, Sir Guy once took under his protection a girl I knew—and was fond of.’

‘Ah—he treated her badly?’

Ophelia gave a short laugh and shrugged. ‘Not according to the notions of a man of his type, I daresay. He kept her in luxury, gave her jewels, furs—you know how it goes.’

Mrs Hargreaves nodded, a reminiscent gleam in her eye.

‘And when he tired of her—he bestowed upon her enough to keep her excellently well—until the next protector should come along.’

‘Then what have you against him?’

Ophelia rose and went to the window, looking out into the night. ‘She loved him—she did not want to go to another man’s bed. And he was cruel. He never answered her letters—’

‘Oh my dear—she did not—not that!’

‘No, no, Ma’am, nothing so tragic. She recovered and made another, even wealthier, conquest. But he was not to know that it would be so.’

‘Well, men are like that,’ remarked Mrs Hargreaves philosophically. ‘Always have been, always will be.’

‘Only because we women put ourselves in their power! That is something I have not done since—’ She stopped suddenly and then continued in a slightly different tone, ‘—since I was very young.’

The older woman nodded her agreement, lips pursed, then as a thought struck her she said, ‘Fanny and he have never met, you say?’

‘No, but Fanny lived in Yorkshire, you know, until her mama died and then was educated in Bath so it is understandable. She came directly from Bath to Brussels with her school-friend’s family, I believe.’

‘And they have never met—’ repeated Mrs Hargreaves in a meaningful voice.

‘No, what—?’ She stopped, meeting the older woman’s eyes. ‘You mean?—no—I could not do it.’

‘Why not? You are an actress. Do you tell me you have never played an eighteen-year-old?’

‘Yes, by candlelight and with the front of the pit standing twenty feet away.’

‘I have seen you in full sunlight and I observed no lines or wrinkles. Your complexion is such as any schoolgirl might envy.’

‘Fanny is a brunette.’

‘Well, but you have your wigs.’

Ophelia stared at her friend. ‘Do you really think I could do it?’

‘How important is it that you should be in London upon July the first?’

‘It means everything.’

‘Then what do you have to lose?’

The following morning, just as the ladies had risen from the breakfast table, there was a peremptory knock upon the front door. Ophelia glanced nervously at her reflection in the mirror that hung above the fireplace and pulled the dark curls that hid her own copper locks forward over her forehead.

She was dressed demurely in a blue and white, sprigged-muslin gown she had worn as Kate Hardcastle in She Stoops to Conquer and which had been hastily altered in the early hours of the morning to bring it into the current mode. Her corset was laced so tightly across her breast as to minimise her principal assets; which caused the breakfast she had eaten so hurriedly to repeat upon her in a distressing manner. Mrs Hargreaves reached over to press her hand in an encouraging way as the ladies heard a quick, firm step upon the stairs and the door opened to reveal a gentleman upon the threshold.

‘Milor Guie de Gilmoire,’ cried the little maidservant, peeping out from behind the gentleman, and fled.

Sir Guy bowed and uttered a curt, ‘Good day, Ma’am,’ to Mrs Hargreaves. Ophelia, glancing at their visitor out of the corner of her demurely lowered eyes, was not sure that she approved of the gentleman. He was about five-and-thirty, tall and well-made with powerful shoulders and a muscular chest. His features were good but his expression was harsh and disagreeable. There seemed a perpetual sneer about his countenance which was, she charitably decided, produced by his high bridged nose, flared nostrils, and the deep lines that ran from thence to the corners of his mouth.

The newcomer was attired for travelling in a well-cut riding-coat of dark blue worsted, buckskin breeches and top boots that had once been highly polished but now, after several days of travel, were lamentably dusty and stained. He held a shallow-crowned beaver in his gloved hand and carried a drab greatcoat over his arm. His dark brown hair was untidy and his cravat creased, as though he could not be bothered to make himself presentable for the inferior company in which he found himself.

His indifferent gaze travelled to where Ophelia was seated and in spite of herself she found herself rising to her feet. She dropped him a little curtsy. He acknowledged it with a slight nod.

‘Well, Miss, I am sent by your grandfather to bring you home. I hope you are ready to set forward immediately. I have no time to waste.’

Ophelia answered in a high, sweet voice. ‘Yes, Sir, I am quite ready.’

‘Who goes with you? Where is your abigail?’

‘I have no abigail, Sir. She left Brussels with the rest of my friends upon the eve of the battle.’

He frowned. ‘Unfortunate! But it cannot be helped. We have no time to engage another. Your trunk?’

‘The boy will bring it down,’ interposed Mrs Hargreaves. ‘Pray you look after her, Sir.’

‘I shall endeavour to do so, Ma’am. Say your goodbyes, Fanny. I do not care to leave the horses in the street. Miserable creatures though they may be, they are worth their weight in gold with the city in this turmoil.’

Ophelia ran to her kind landlady and friend with her arms open. The two women hugged and promised faithfully to write every day. But Sir Guy’s slightly contemptuous stare was not favourable to sentiment. After a few moments they drew apart. Ophelia donned her bonnet and pelisse, gave her friend one last wave and meekly followed Sir Guy out of the room.