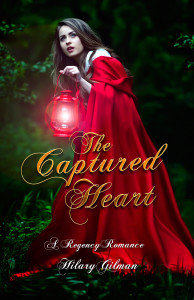

The first chapter of The Captured Heart

The Captured Heart is almost ready, I hope to publish at the end of this week. In the meantime, as usual, I’m posting a snippet (and once again, sorry about the formatting. It goes wonky when I post it here.)

*****************************************************

‘You are far too young to be a governess.’

Cecily Danvers knew only too well what that meant: she was not too young, she was too pretty. Far too pretty to be employed in any household that included an impressionable male. In her experience, this meant almost every home where a governess was required, since children inevitably possessed fathers, brothers, and even, she repressed a shudder, grandfathers.

Nevertheless, she must try. She clasped her mittened hands in her lap and raised soulful eyes to the face of the elderly gentleman behind the desk.

‘Not—do you think—to be a nursery governess? I am very good with little ones. I have brothers and sisters of my own, you see.’

‘Then why are you not at home tending to them?’

Cecily would very much have liked to tell this detestable old man to mind his own business; but, if beggars cannot be choosers, they must equally swallow their pride and answer impertinent questions. ‘I am the eldest daughter, indeed, the eldest child, and I need to earn my living and relieve my dear Mama of the charge of my upkeep.’

‘I see.’ Hard grey eyes examined her through steel-rimmed spectacles. ‘Do you object to travelling into Lincolnshire?’

‘Lincolnshire!’ I did not know—had no idea—it is not specified in the advertisement.’

‘So you do object?’

‘I—no—no not at all. It is just that I thought the position would be in London.’

The lawyer picked up a paper and perused it. ‘The position is that of nursery governess to Robert, Lord Fanshawe, the fifth baron, a boy of five. You would live with the child, his nurse, and his grandmother at Heron Lodge, just outside Alford in Lincolnshire. His grandmother is an invalid, and you would therefore, be responsible for all aspects of his care other than that provided by his elderly nurse.’

Cecily thought that a drearier prospect had never been dangled in front of her. There was only one inducement that might lead her to accept the position: ‘What is the salary, if you please?’

The gentleman appeared to approve of this business-like attitude. ‘One hundred and fifty pounds per annum.’

Cecily’s mouth fell open in astonishment. This was munificent—incredible! In her previous position she had been paid a measly forty pounds a year and considered herself fortunate. ‘I shall take it!’

‘Yes, I thought you might.’

‘When would you like me to start?’

Cold grey eyes met hers for one unnerving moment. ‘The stagecoach leaves at nine o’clock tomorrow morning from the Golden Lion in Holborn. Here is your ticket.’

He took a key off his gold watch-chain and unlocked a little drawer in his desk. He brought out a roll of bills and peeled five pound-notes from the top. ‘For expenses,’ he said, handing them to her.

Cecily took the ticket and the notes, thrusting them into the little sealskin muff she carried. ‘Thank you. I will be there.’ She stood and dropped a little curtsey before making for the door. Then, quite suddenly, she stopped. ‘You had the ticket ready. How did you know I would accept the position?’

The lawyer smiled grimly. ‘There are three more young women waiting in the outer office. I have seen five already this morning. You fulfil the requirements admirably; but, if you had turned it down, one of the others would do.’

‘The family is very anxious to hire a nursery governess for this child.’

‘I am very anxious.’

Cecily wrinkled her brow and said in a diffident voice, ‘Is there anything I should know—that you haven’t told me, I mean?’

He hesitated, ‘Nothing that need concern you now. You will be more fully informed upon your arrival.’

‘Oh. Well, thank you. I trust there will be someone to meet me at the coach stop?’

‘Everything will be seen to.’

‘Good—excellent—thank you, Sir.’ She offered her hand and dropped it after a few moments when the gentleman made no move to take it. ‘Goodbye.’

She received a curt nod as the lawyer sat down and began to write. Cecily opened the door, passed out into the vestibule, and shut the door behind her with a decided snap. Odious old man!

She left the building and turned right down Piccadilly. It was a cold March morning, with a gusting wind lifting the skirt of her pelisse and making the single ostrich feather in her bonnet wave wildly. The bright, cold air had whipped a fresh colour into her cheeks, and her big dark eyes shone with triumph. Her dusky curls beneath the rather old-fashioned quilted bonnet—it had been her Mama’s—were charmingly disarrayed. She fairly ran down the street, too excited to be conscious of the admiring looks of various gentlemen passing by.

Presently, she turned down Bond Street and walked briskly to a haberdashers about halfway down the street. There was a narrow door between the plate glass window and the entrance to the adjoining establishment. She let herself in with her latchkey and ran up a staircase, unlit save for the pale sunshine that came through the fanlight at the top of the door. As she reached the landing, she called out, ‘Mama! Mama, I got it. I got the position. And it is a hundred and fifty pounds a year!’

A door opened, and a lady appeared on the threshold. In that dim light, the two women might have been sisters. ‘My dear child, come in and warm yourself,’ Mrs Danvers said in a low, sweet voice. ‘I have some coffee here and can heat up the hot milk in a trice.’

‘But did you hear what I said?’ Cecily put her arms about her mother and hugged her. ‘All our troubles are over.’

‘Now what would your father have said if he could hear you?’ Her mother lovingly untied the strings of Cecily’s bonnet and laid it aside. ‘You know how he was.’

Cecily unbuttoned her pelisse and tossed it onto the back of a chair. She sank down in front of the fire and held her hands to the blaze. ‘He would have said that our troubles are solved, not by money but by prayer.’ She looked up mischievously, ‘But I prayed for the money, so that is all right.’

She accepted the cup her mother proffered and, holding it between her chilled hands, blew upon the hot coffee before taking a sip. ‘I must be ready to start for Lincolnshire tomorrow, Mama. But I have scarce unpacked anything since we came up from Hertfordshire, so it will not take a minute to have my trunks corded and—’

‘Lincolnshire?’

Cecily’s dancing smile faded a little. ‘Yes. I know it is a very long way, but perhaps I may be allowed a holiday after a year or so and may come home for a visit. And I will write to you every day, I promise. Oh, Mama—dearest, don’t look like that.’

‘Forgive me. I know it must be so. You must always have left home wherever your position. It’s just that— Oh, how am I going to manage the children without you?’

‘Molly is grown up enough to take my place. And, with the salary I am to receive, I will be able to send you enough to hire a little maidservant to help you around the house.

Mrs Danvers smiled and reached forward to pat her daughter on the knee. ‘The children do not mind Molly as they do you. She is such a hoyden. But there, Jeremy will be going for a midshipman next month, and Baby Alice has been weaned. I daresay it will not be so hard.’ She sighed. ‘Your Papa was a saint, and I know he did not mean to leave me alone with twelve children on my hands. But, oh, how I wish he had never gone to that horrible old woman’s deathbed, and—’

Cecily took her mother’s hands in hers lovingly. ‘Hush, Mama. You know she wasn’t a horrible old woman. She could not help taking the typhus. And a clergyman must go among the sick.’

She patted her mother’s hand and stood. ‘That nasty lawyer gave me five pounds, as well as my ticket—for expenses—so I propose we have our breakfast and then go out and buy me a new bonnet. Because, although this one is very suitable for a young lady in search of a position as governess, you must have it back, and none of mine are governess-ish at all.’